INDIANAPOLIS—When e-cigarettes first hit the market, manufacturers sold them as a cleaner, safer alternative to combustible cigarettes. They targeted current smokers, touting vape as a good way to quit.

“But that is clearly not how they are being used,” says Amy Peak, Butler University’s Director of Undergraduate Health Science Programs. Her recent research about the harmful effects of vaping included a survey of nearly 1,000 college students.

Peak recently completed this large-scale study in collaboration with Sarah Knight, a senior Health Science major, and they presented their findings at the 2019 Indiana Life Sciences Summit on September 26.

They discovered that, while vaping was originally promoted as a safer alternative for existing smokers, most young vape users are brand new to nicotine. And it probably isn’t any safer, either, with most users experiencing a variety of harmful effects.

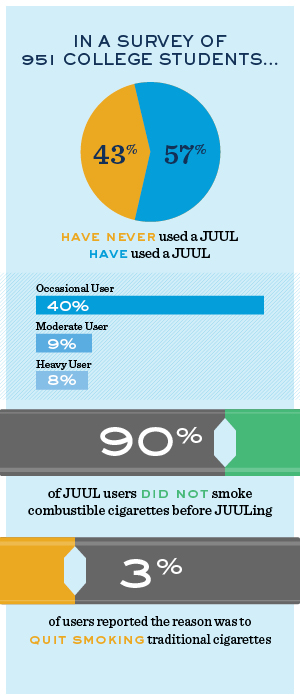

In data gathered throughout the past year, Peak found that almost 60 percent of college students had used a JUUL—the most popular e-cigarette in the United States. Of the students who vaped, 90 percent had never smoked a traditional cigarette. Only 3 percent of respondents said they used JUUL in an effort to quit smoking.

“Vaping is clearly an entry-level thing,” Peak explains. “It is not something that the college population is using as a smoking cessation product.”

And for pretty much everyone who vapes, even occasionally, there are consequences.

The most common adverse reaction found in Peak’s study was coughing, a symptom reported in about a third of all users. Other common harmful effects included nose or throat irritation (20 percent of users), headaches (18 percent), shortness of breath (16 percent), and difficulty sleeping (6 percent). For most of these effects, Peak found that the more often someone vaped, the more likely they were to experience these side effects.

Nicotine withdrawal was also common, affecting 72 percent of heavy users, 54 percent of moderate users, and 8 percent of occasional users. Reported withdrawal symptoms included cravings, headaches, mood changes, and the inability to think clearly. Peak explains that the form of nicotine used in JUUL pods provides a faster, harder hit than combustible cigarettes, which makes vaping more addictive per use than smoking.

“There is no doubt that this is an addictive substance,” she says. “It is something that people are going to have substantial trouble coming off of if they are using it regularly.”

The study also found that almost all college students who vaped had done so in a social setting, sharing e-cigarettes with others, which could contribute to the spread of infectious disease. Of the respondents who used vaping products, 95 percent had put a JUUL in their mouths immediately after it was in someone else’s mouth. Peak says this could spread any form of bacteria or virus that is transmitted via saliva, including some forms of herpes, mononucleosis, influenza, norovirus, or strep throat—just to name a few. This risk of spreading infectious disease is not typically seen with combustible cigarettes.

“That, in and of itself, I think is a public health hazard no one is talking about,” Peak says.

Going forward, Peak plans to partner with Butler Biological Sciences Lecturer Mike Trombley to look deeper into that infectious disease potential.

Before collaborating with Peak on this research, student Sarah Knight had noticed many of her college-aged peers starting to use JUUL without knowing much about it. She wanted to help fill gaps in existing research about the risks of vaping, and she enjoyed the chance to be part of something that has such an immediate impact on public health.

“There is a misconception that vaping is a safer alternative to combustible cigarettes,” Peak says. “My hope is that, as this data comes out, we have mounting evidence that changes this idea.”

She explains that most people assume that just because you don’t see smoke or smell tar when using JUUL, it must be safer than a combustible cigarette. This has created an environment where vaping is a lot more socially acceptable than smoking.

“But this is just a different delivery device for an incredibly addictive substance—and a substance that is mixed with flavorings and colorings that have no business being inhaled,” Peak says.

Those candy-like flavors—now facing a potential ban—have made JUUL especially appealing to young people. And as new lung illnesses have brought vaping products under more nationwide scrutiny in recent weeks, Peak hopes this study will join the conversation in a way that helps teens and college students understand that adding an “e” doesn’t make cigarettes any safer.